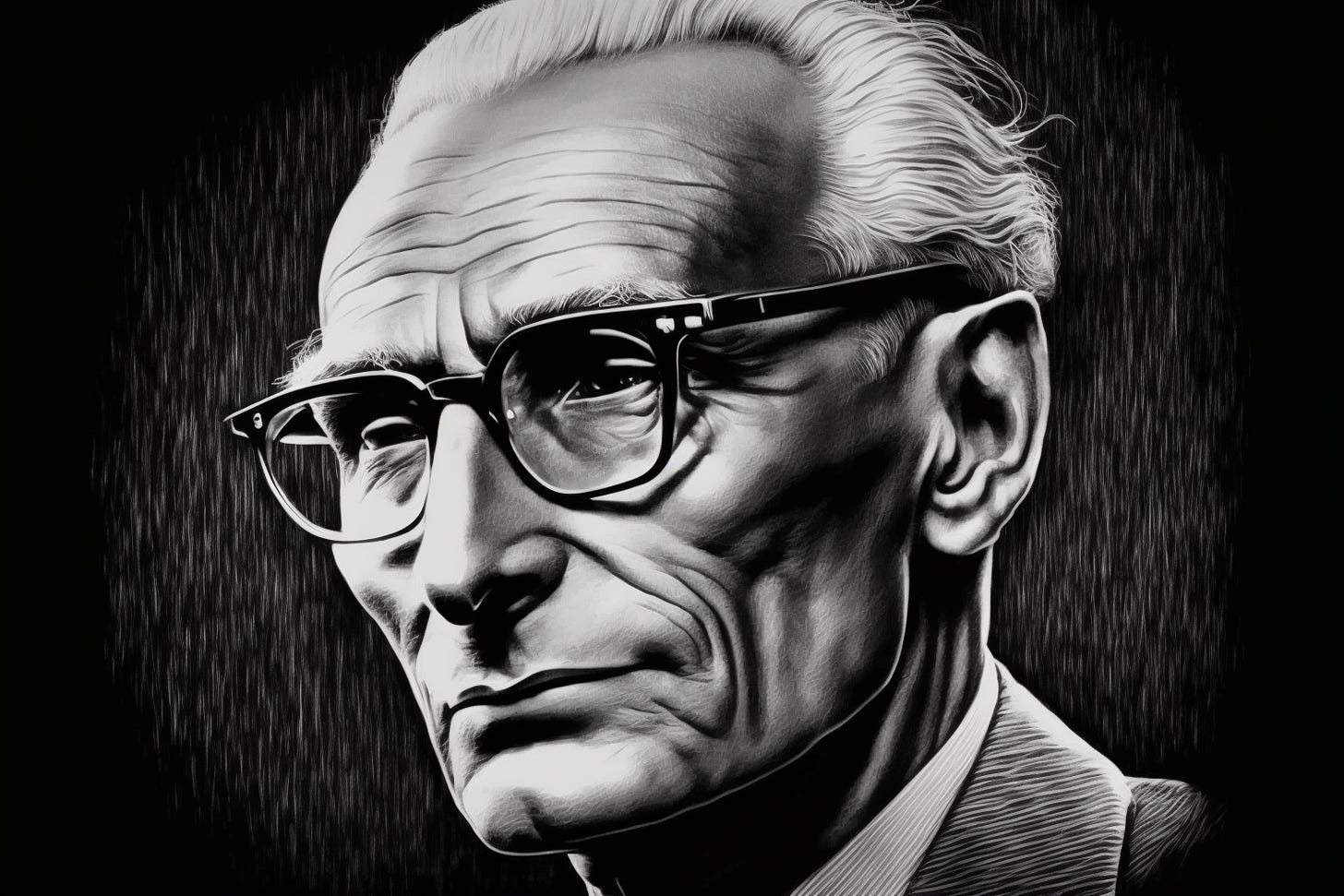

Who is Claude Lévi-Strauss

Exploring the Life, Work, and Legacy of the Renowned Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss was one of the most influential figures in 20th century anthropology. He is best known for introducing structuralism to French intellectual life, which is a method of analyzing social institutions and culture by looking at patterns and structures instead of individual elements or components. Born on November 28, 1908 in Brussels, Belgium, Lévi-Strauss developed an early love for literature that laid the foundation for his later work as a philosopher and anthropologist.

His journey into academia began when he attended college at University Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne where he received degrees in law (1931), philosophy (1932), and psychology (1935). During this time period it became evident that there was significant disparity between European scientific discourse about ‘primitive societies’ and what actually existed within them, sparking his interest in ethnology/anthropology. Claude eventually accepted a position as Professor of Sociology at São Paulo (Brazil) from 1935–39 before moving back to France where he served as Director of Studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Études until 1962 and then subsequently became the chair for Social Anthropology at the Collège de France until 1982 when he retired from active teaching duties but continued to lecture publicly into his nineties!

From 1946 onward Lévi-Strauss Published many works including: The Elementary Structures Of Kinship in 1949, Totemism in 1964, and his magnum opus – The Raw And The Cooked – in 1964 as well as Mythologies published between 1964-71. All these works had a strong focus on structuralist analysis which revolutionized our understanding of the study of ethnography by applying the thinking on patterns of culture across various societies around the globe.

This approach was necessary because while there is amazing diversity amongst different cultures around the world it is possible to compare them using common language structures of ideas on a more sophisticated level than mere observation of facts. When looking at language for example, Lévi-Strauss emphasizes that there are some basic linguistic shapes which are universal. All speech acts through their syntactical arrangement. What is interesting is that this universal language structure can be used to interpret signals conveyed in cultural activities such as a mouse hunting song etc.

Many scholars from different disciplines continue to build upon his work in order to better understand what it means to be a human being living within society today.

One major contributor who expanded Claude Levi-Strauss’ ideas was French philosopher Jacques Derrida who wrote extensively that there exists an inherent conflict between structure (which he believed was determined by language) and meaning (which could only be accessed through deconstruction). This idea has since been used by various academics in their research regarding identity formation among minority groups or subcultures across societies which often fail to conform with traditional norms. Those thinkers are instead exploring where we draw boundaries when talking about cultures.

Similar notions were explored later on by postmodernist theorist Michel Foucault whose concept “bio power” further developed this notion that individuals exist both inside cultural parameters but outside those too depending on context.

Additionally, postcolonial theorist Edward Said argued against European imperialism while addressing issues related to racism associated with colonization. Jean Paul Sartre is another academic who applied Lévi-Strauss’ theories in arguments he put forward during WWII in France as he worked to discredit the Nazi regime and its oppressive policies towards Jews, Roma people, etc.

There are many important ideas we can learn from Claude Lévi-Strauss’ work – here are three of them:

First off is that human societies have an inherent structure which shapes how people act within it. This has become known as structuralism or “structural anthropology” in reference to Lévi- Strauss' approach. For example, he identified recurring patterns in kinship systems across cultures – something notably different than the functionalist theories popularized earlier by Emile Durkheim who instead argued that functions existed independently of their form (e.g., roles determined appropriate to their relationships). Structuralists like Levi–Strauss focus on understanding underlying similarities between seemingly disparate elements rather than surface differences based upon outward appearances or behavior alone.

Secondly, one should remember that customs and traditions do not exist without history but persist because they fit with existing values over time. This means that traditional behaviors aren't inherently good or bad per se but must be viewed relative to changing circumstances. This idea was first articulated fully in The Elementary Structure Of Kinships where he showed how similar marriage norms could go through dramatic change when trading partners changed due simply to altered interests among members involved (i.e. exchanges causing shifts away from reciprocity towards individualized benefit).

Lastly, taking into account both points above implies a need for us all to accept our responsibility for actively working together if desired outcomes are going to achieve success. Functionalists might propose solutions rooted solely on empirical evidence/observation while structuralists might find some value in trying to identify longer term connections that are often overlooked initially. The key insight being then, that progress isn't guaranteed just because governance models composed of “elite” men will automatically generate positive results unless those same individuals are genuinely committed to making sure that happens!